Over the summer of 2023, in stadia across Europe and North America, and projected in colossal scale on LED screen backdrops 15 meters high, two panels extending on either side of a central, circular portal, a woman in an electrode-adorned crown of chrome taps on the fourth wall. The membrane of light does not long divide her from her audience. The central aperture opens, and a contraption slides Beyoncé toward the crowd. The voice of Kevin Jz Prodigy announces, “EVERYONE, welcome to mother’s mind.” Then asks, “Are you ready to serve?”

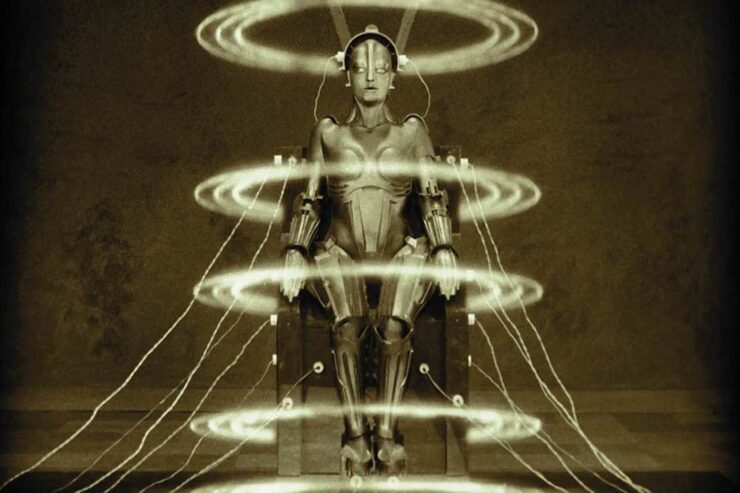

So, this will only be about the five-thousandth piece to note that the set and costume design accompanying Mother’s Grand Entrancé on her Renaissance tour pays homage to Fritz Lang’s 1927 science fiction classic, Metropolis. Specifically, Beyoncé adopts the iconography of the Maschinenmensch, the artificial robot woman who is central to the film’s plot—though is not, as I have seen misstated elsewhere, the film’s protagonist. I swear I’m not just nitpicking; this will be important.

The robot, named “Futura” in the novelization by Thea von Harbou (who also wrote Metropolis’ script alongside Lang), is a tool of exploitation. Conceived of by evil inventor Rotwang (Rudolph Klein-Rogge) as a replacement for the already exploited workers of the fictional city, she is ultimately utilized by the chief capitalist, Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel), to supplant the workers’ spiritual leader, Maria (Brigitte Helm), by stealing her identity. In the film’s most famous scene, Rotwang and Fredersen give a sort of proof of concept for their plot by having Futura-qua-Maria perform a seductive dance in the ritzy Yoshiwara club, where her sexy gyrations drive the assembled men into fits of drooling madness.

Knowing this, purists and pedants alike (and I self-identify as both) might be tempted to smugly titter at performers who adopt Futura’s image, visually aligning themselves with a character who is a tool of devious corporate overlords looking to undermine critical thinking. She is literally an industry plant.

But symbols are rarely static, and in the intervening near-century since the premier of Lang’s film, the popular perception of the figure of the robot in general and of Lang’s Maschinenmensch in particular has shifted—in no small part because of artists like Beyoncé whose adaptations don’t merely invite us in on a fun reference but ask us to see it from a different perspective. The available references to Metropolis and Futura are numerous, even if we restrict ourselves to the realm of music. To give just the latest update, Zendaya recently graced the Dune: Part Two world premiere’s red carpet in London wearing a vintage bodysuit designed by couturier Thierry Mugler to reference Lang’s famous Maschinenmensch. In fact, Zendaya’s fashion choice provides us with a handy demonstration of how Futura has managed to recur as an influential icon across the decades: designed by artist Walter Schulze-Mittendorff in 1927, referenced by the fashion designer Mugler in 1995, and resurrected by the actress Zendaya here in 2024.

For today, though, we will focus on just three key Futura references from three recording artists: Whitney Houston, Janelle Monáe, and Beyoncé, all of whose extended adoptions of Futura as a performing persona comment on the performer’s relationship to their audience, exploring the robot not in her capacity as a villain but rather as a locus of attention. Metropolis demonstrates the power Futura has on other people; the pop star, crediting Futura with her own interiority, questions what effect the gaze of the public has on her.

Whitney Houston: Queen of the Night

Premiering in 1992 and working from a script that writer Lawrence Kasdan had originally written in 1975 (initially pitched as a vehicle for Diana Ross and Steve McQueen), The Bodyguard was the film debut of Whitney Houston, arriving on the tails of her third studio album, I’m Your Baby Tonight. Even if you aren’t versed in Houston’s discography, and probably even if you aren’t from a generation that was beholden to radio, you’ve regardless definitely heard “I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)” at least a hundred times. This is all to illustrate (unnecessarily, given the fact) that Houston was a huge pop music star, and this film arrived when she was very much a reigning voice in popular music, and certainly the biggest voice if we go purely by the power of her instrument. So she was a natural choice, and reportedly star and producer Kevin Costner’s only choice, to play the role of Rachel Marron, pop idol and Oscar-nominated actress.

The plot of the film revolves around the relationship between Rachel and the titular bodyguard, Frank Farmer, whom she hires at the urging of her manager after receiving anonymous death threats. Or to borrow the phrasing from Costner in the making-of documentary, “he [Frank] has this huge problem of protecting this chick that’s being an absolute bitch to him.” By the way, this film is a romance; they fall in love.

The gender politics of this movie, and indeed of the entire ’90s, have not aged great. Kasdan and Costner, the two dominant creative voices, were very taken with the figure of the Kurosawa samurai, this warrior utterly unafraid of death, which they translate into the character of the bodyguard for hire. It’s an influence the film subtly nods to by having Frank take Rachel on a date to see a screening of the film Yojimbo,the title of which translates literally to “bodyguard.” Then they repair to Frank’s house, where he shows her the samurai sword he has hanging up in his otherwise barren-ass basement. THEN Frank demonstrates that he apparently keeps this for-display katana fastidiously sharp by using it to cut Rachel’s scarf—which looked like it was a nice scarf, and he does not ask permission first. But whatever. She’s into it. They hook up. Then, on the very next day, immediately after rolling out of bed, he breaks things off with her. That’s not part of the samurai reference, it’s just the final incredible detail in an incredible sequence of events. This movie is terrible. I love it.

But apart from the Kurosawa references, The Bodyguard features one other major cinematic allusion—specifically to our subject, Lang’s Metropolis. Occurring around the end of the first act, the “Queen of the Night” sequence serves as the first major test of Frank and Rachel’s working relationship. It is the first public event at which he must protect her, the premiere of her new music video at a nightclub, and also the first occasion where she becomes aware of the threats against her life, reframing for her character all of the rabid attention she is receiving.

Despite the threats and Frank’s objections, Rachel chooses to go forward with the performance. Shots of Rachel, costumed in metallic chest- and head-pieces that evoke Futura, dancing and singing on stage are intercut with clips from Futura’s lurid dance in Metropolis projected on the screens behind her.

And here the filmmakers have pulled off something really quite clever in not merely citing an apt reference—Rachel, like Futura, is presented as regularly driving her audience out of their coconuts, while she is herself manipulated by an ambitious, Rotwang-ish publicist—but in recontextualizing the images they draw on in an interesting way.

Even amidst the rapid editing, of all the shots recycled from Lang, one in particular stands out, a collage of the leering eyes of the men from the Yoshiwara club. It’s a shot that in Metropolis emphasizes the hypnotic power of Futura’s dance, as the viewers are stripped of the individuality of a complete human face, reduced together to a mass of looking. This implication is not gone when the shot is translated into the scene in The Bodyguard, but in the context of the pre-established threats against Rachel’s life, it takes on an additional layer. The image of the eyes, already ominous in Lang’s film, suddenly feels more hostile, as we are conscious of the fact that someone in this club means this Futura real harm, and that lurking danger pollutes the general act of gazing. It’s a change that shifts the audience’s allegiance toward the performer, Houston/Rachel/Futura, by asking us to sympathize with her precarious position. It is her role to be seen, and heard—but by a crowd that might hide malicious actors, turn against her, or overwhelm her with their attention, all three of which, after a fashion, happen in the scene.

This paradigm that adapts Futura into more than a vampy seductress, into a woman held hostage by her own popularity and the combined power and resentment that it brings, might be a suitable or appealing persona for any famous person, but it holds some particular resonances with the career of Whitney Houston, whose relationship to her public was fraught even before her much-covered “downfall” in the late ’90s and early 2000s. In his 2022 biography of Houston, Didn’t We Almost Have It All, music journalist Gerrick Kennedy relates how Houston was from the start of her career dogged by criticism for not being as artistically bold as her contemporaries like Madonna or Janet Jackson, lending fuel to the narrative that she was little more than a cypher being programmed for maximum crossover appeal by Arista executive Clive Davis.

We may well make a comparison of Houston with Madonna, whose 1989 music video for “Express Yourself” also pays homage to Metropolis. Assuming the vampy Futura persona would have seemed a more obvious choice for Madonna, whose public image was far more associated with controversial, sexually suggestive and explicit gestures. But rather than droid-ing herself up in chrome, Madonna strips down and presents herself chained to a bed. It’s the same sort of risqué move that tended to earn her both attention from scandalized audiences and credit from critics. Caryn James, dissecting an interview Madonna gave to ABC News in 1990, writes how Madonna “made a distinction any honest feminist would respect. ‘I have chained myself,’ she said. ‘There wasn’t a man that put that chain on me.’” (Bit of a No True Scotsman fallacy there, but never mind that now.)

Houston’s image, meanwhile, was tamer, less outrageous, and for that, seemingly less self-assured and self-determined in her choices. Indeed, there was speculation that too-wholesome Whitney, whose bread and butter was romantic (but not sexy) ballads, was repressing or withholding something of her nature. Rumors swirled, and then were concretely inked in the press, that Whitney was gay and that her friend and executive assistant Robyn Crawford (described in Time magazine’s coverage as “severely handsome”) was secretly her lover. Crawford has since confirmed they did have a relationship, though she explains that she and Houston were not actually together concurrently with Whitney’s music career, a career that was taking off at the same time that AIDS epidemic was driving a national moral panic around homosexuality. The demand, then, was for Whitney Houston to embrace greater artistic authenticity by acknowledging a truth for which the public might well have damned her.

An additional confounding issue for Whitney, not faced by Madonna, was her Blackness, which created tension between her and Black critics who felt that she had sold out by curating her image and music for a white mainstream audience. Kennedy describes how:

Because Whitney was engineered for pop audiences there was this expectation that she needed to be all things to all people—expectations heightened by the fact that Whitney was a Black woman clamoring for airplay and MTV spins alongside mostly white acts. To be a woman in pop meant exhaustive comparisons to any other woman in the industry, defined by what qualities they did or didn’t have. Here was a graceful singer with an extraordinary pedigree making sweet, romantic soul music and joyous dance anthems, but it was who she wasn’t that became the fascination of critics unconvinced that a Black woman wanted to sing these tunes.

Whitney, then, was maligned as a sort of automaton: unprecedentedly popular, and yet more of a creation than a creative. It was almost certainly inadvertent that The Bodyguard’s filmmakers, who avoided broaching the subject of race in the film and were more invested in exploring the figure of the bodyguard than the superstar, came up with an image as compelling as Whitney-Futura: the star who mesmerized us with her voice, her charisma, her beauty, but whose perceived lack of authenticity we held against her. We wanted her to own her Blackness, heedless of what that part of her identity really meant to her, and to own her sexuality—or, more likely, to more convincingly disown her perceived homosexuality.

In that context, the android persona here feels almost like a defiant embrace of artifice, a reversal of the Futura of Metropolis, exposing rather than concealing the mechanisms of performance. Part of that exposure throws our own gaze back at us, and the sight is distinctly unflattering. There we are, an undulating mass groping with our eyes, hungry for realness, unforgiving of reality.

Janelle Monáe: Our Favorite Fugitive, Cindi Mayweather, Alpha Platinum 9000, Electric Lady Number One, and the ArchAndroid

If you’ve been in Metropolis in the year 2719 and ever happened to tune into 105.5 WDRD, then you must have heard about Cindi Mayweather, Electric Lady Number One.

But residents of 2024 may be more familiar with Janelle Monáe, acclaimed recording artist (and actor) whose first three releases, one EP and two full albums, adapt Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. In this series of concept albums, collectively referred to as the “Metropolis saga,” Cindi is Monáe’s avatar, an android from the future—and also a popular songstress of her time—whose robot nature and messianic role parallel and commentate on her 1927 counterpart, Futura.

The influences Monáe draws on in their own sci-fi sonic worldbuilding are much more extensive than just Lang, involving nods to Octavia Butler, Lewis Carroll, Philip K. Dick, Jimmy Hendrix, George Clinton, Sun Ra, David Bowie, Marvin Gaye, and The Matrix, to name just a few. Still, Metropolis remains the spine of the narrative, with Monáe adapting its themes of oppression, its romanticism, and its biblical gestures, and this time casting the exploited android as the heroine and savoir, rather than reserving that role for a scion of the elite like Lang’s protagonist, Freder.

Monáe’s interpretation is deft in how it retains many of the artifacts of Lang’s original while reimplementing them in more thoughtful, critical ways. For instance, Cindi (like Futura) is a face-stealer, her “organic compounds” having been cloned from—who else—Janelle Monáe (who has been sent back to the present from 2719—it’s a whole thing). But the audience is conscious of Cindi’s having no choice in coopting Monáe’s face, much as Futura had no choice. Modern viewers of Lang’s film are, I suspect, likely to note this, having been trained as savvy SF readers to empathize with artificial intelligences. But for all that, the original Futura remains a vapid and inaccessible character, not the self-reflecting sort. Cindi meanwhile bursts onto the stage, and into our ears, dialectically constructing her sense of self out of the artificial non-identity that society has foisted on her:

I’m an alien from outer space,

I’m a cyber-girl without a face,

a heart, or a mind (I’m a product of the man).

I’m a slave girl without a race

On the run cuz they’re here to erase

And chase out my kind (they’ve come to destroy me).

And I think to myself

Wait, it’s impossible…

Oh, she’s a thinker for sure. Throughout a text that can in places be quite densely detailed, Cindi’s cogitations keep us oriented. If you lose track of what a Wolfmaster is or aren’t sure if it’s important that androids apparently have gray hair, you don’t have to worry. So long as you’re still vibing with Cindi’s feelings, you’re never really lost.

The main feeling that animates the albums is the conflict between Cindi’s desire for personal happiness and her higher calling to fulfill the role of the ArchAndroid, the prophesied revolutionary savior to android kind. This tale’s inciting incident, detailed in the track “March of the Wolfmasters,” is the forbidden love affair between Cindi and the human Anthony Greendown: “And you know what that means! She is now scheduled for immediate disassembly!” Here again the plot parallels Metropolis 1927, wherein Freder’s love-at-first-sight encounter with Maria prompts his own radicalizing journey. Only the love is more fraught for Cindi, incurring violent legal consequences that recall real-world historical anti-miscegenation laws. The taboo nature of the relationship has also received a queer reading from critics and audiences, bolstered by scattered lyrics like “Is it weird to like the way she wear her tights?”

Cindi and Sir Greendown’s union, matter of true love though it may be, seems doomed not only by the evil government but by fate, as Cindi is drawn into—and isolated by—her role as the ArchAndroid. On the track “57821,” the refrain “He wonders if she is the one / She wonders if he is the one,” eventually resolves to “I wonder if I am the one.” The common (monogamous) romantic trope of “the one” that Greendown and Cindi use to refer to one another is superseded by a different trope, the chosen one, this time with Cindi referring only to herself, speculating on her possible destiny as savior. That metaphorical, grammatical separation between them becomes literal on the final track of The ArchAndroid album, “BaBopByeYa,” in which Cindi reflects on her and Anthony’s romantic history. Ultimately, and fatalistically, she feels pulled away to serve the higher calling and greater good: “I see beyond tomorrow / This life of strife and sorrow. / My freedom calls, and I must go.” It’s a bittersweet and resigned ending, one that then recurs in the sequel album, The Electric Lady, with the one-two punch of “Can’t Live Without Your Love” followed by “Sally Ride” (“I know you love me, but I’m still gone,” Monáe-as-Cindi chants on the latter).

It’s a much stronger and more emotionally resonant conclusion than the one delivered in the 1927 Metropolis, where Freder “mediates” away all conflict without instituting any real change to the hierarchies that have troubled the city, leading to the maudlin aphorism that “the mediator between the head and hands must be the heart.” Monáe meanwhile does not disavow romantic notions like true love or heroism, but she makes honest concessions in acknowledging how movements for change require sacrifice—and how some people will disproportionately bear the burden of that sacrifice.

We could go on enumerating the ways that Janelle Monáe adapts Metropolis and Futura, how the album art and trailer for The ArchAndroid reference and synthesize the elements from Metropolis’s iconic poster, how the “Many Moons” short film expands on the model of Futura’s dance at the Yoshiwara club, or how the track “Look Into My Eyes” subverts the stereotype of the hypnotic vamp.1 I’ve focused on Monáe’s depiction of Cindi’s consciousness, however, for how it parallels our earlier discussion of Whitney Houston in expressing the psychic toll borne by the Black female artist under pressure to dazzle, to lead, to inspire, to represent.

Since the turn of the decade, spurred by mainstream re-engagement with the movement for Black civil rights in the wake of the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in May of 2020, there has arisen this pernicious narrative in some liberal circles about how Black women will “save us” by diagnosing and reforming societal ills. It’s a narrative—or a plea, really—that is often couched in laudatory language but which ultimately punts responsibility for driving broad social change to that one demographic without prioritizing their specific needs. In that context, Cindi Mayweather feels timely, future femme though she is, as a Black heroine who is very much acting in her own self-interest insofar as the community she seeks to liberate are the other androids, yet still it’s costly.

Monáe came out as non-binary in 2022 and as pansexual in 2018. Their sexuality has been the subject of speculation and scrutiny since their first release, with evidence mustered like the predominant queer themes in their work and Monáe’s penchant for tuxedos and other androgynous style choices. Here again we have to think of Whitney Houston. Yes, it’s generally safer to come out now than it was in the 1980s or ’90s, but it remains invasive to insist that someone publicly “clarify” their orientation or identity. As obvious or inevitable as it may have seemed that Monáe would come out eventually (and as someone who was listening to The Electric Lady on repeat in 2013, I can attest that it felt that way), even if it looked like she was intentionally dropping breadcrumbs to that effect, the coverage seems to have worn on her, receiving a justifiably snappish callout on “Float,” the leadoff track to her latest album.

In her last two releases, Monáe has also distanced herself from the Cindi Mayweather persona, first with Dirty Computer and its accompanying film, which keeps the rebel android theme but changes the artist’s persona to simply “Jane,” and then in 2023’s The Age of Pleasure, which does away with the futuristic premise altogether. It’s a shift that is, probably not accidentally, concurrent with the artist’s recentering their own peace (and pleasure) against former aspirations of saviorhood.

The topic of the interface between audience and creator, though, is still very much in play. There’s a shot in the music video for “Lipstick Lover,” the second single from The Age of Pleasure, that stands out: The setting is a paradise pool-party orgy, and the camera guides us around the scene of dancing, feasting, and bare flesh. Exhibitionism seems like the order of the day; then the camera cuts to a group of lovers in a hot tub. As a spotlight passes over them, they startle and look up into the lens, the eye of the viewer, with mixed expressions of surprise and censure. It’s a discomfiting moment that keeps the experience from being wholly voyeuristic. Our presence has not gone unnoticed.

Between Cindi’s tribulations and Monáe’s more straightforward recent expressions, it’s the second time that a Futura has forced us to catch ourselves looking and made us self-conscious. Inherent in that capacity is the acknowledgement that she has the psychology and personhood to merit that sense of self-consciousness on our part. No longer is Futura the hollow vessel or flat surface onto which we can project our fears, lusts, and hopes. She has a cyber-soul, and you will show her respect.

Beyoncé: Renaissance Woman and Alien Superstar

I take it I don’t have to explain the Beyoncé phenomenon to anyone? I’m already hesitant about getting into too much detail about Janelle Monáe’s oeuvre, which has never quite broken fully into the mainstream but is hardly obscure. If you’re like me—well, you were generally aware of Beyoncé as part of Destiny’s Child and then as a solo artist consistently on Top 40 radio, but didn’t get especially invested in her output until her excellent eponymous album in 2013. (I did recently go back and listen to all of B’Day for the first time, though, after reading Daphne Brooks’ analysis of the album, and I really enjoyed it.)

If my own journey can be said to be representative—and feel free to take that premise with a convivial lump of salt—then the trajectory of the culture’s relationship to Beyoncé has moved from enjoying her as a reliable hit-maker producing solid, non-groundbreaking pop to embracing her as an artist worthy of more wholistic treatment and higher regard. The deep cuts became mandatory listening.

Take for comparison the Beyoncé of the 2000s and early 2010s next to a more outrageous act like Lady Gaga—in a way, the Whitney and Madonna of our time. The former flaunted an awesome melismatic vocal style, elevating romantic ballads that could otherwise be too boringly classic, while the latter leaned into provocative, queer, and avant-garde choices. See: Meat dress. But after more than two decades of proven staying power and the watershed release of Lemonade, it’s become undeniable that Beyoncé has (always had) keen musical instincts and a real desire to pursue her own artistic fulfillment. And that pursuit has paid off. The only other act in the business that can compare with her now in terms of influence is not Gaga but the younger Taylor Swift.

After thriving in the limelight for so long and in course having only been hoisted farther up on the proverbial pedestal, accumulating a hive of die-hard fans, Beyoncé has more than earned the right to don the chrome crown of Futura. (No justification was necessary, but even so.) The Renaissance World Tour isn’t the first time in her career that she has drawn on the imagery of Metropolis and the Maschinenmensch—witness her performance at the 2007 BET Awards, when she emerged from a similar contraption to the one used on her tour…and if there’s one thing Beyoncé and Beyoncé fans all really enjoy, it’s a Beyoncé deep cut. But this time the Futura reference was more sustained and integrated into the larger thematic project of the Renaissance album and tour, with the android persona presenting a clever rhyme with the album’s electronic dance music influences, generally adding another layer of entendre to the proceedings—“Are you ready to serve?”—while also being neatly symbolic of the idea of a “renaissance” itself. If a rebirth represents the meeting point of past and future, who better to embody its contradictions than retro-futurist robot lady, Futura? She’s a throwback, she’s the unrealized potential of tomorrow, and she is the moment.

Surviving the vicissitudes of the public eye for so long seems to have motivated that rebirth ambition for the Bey Hive’s queen, who discusses the toll that her career has taken on her body in the Renaissance concert film and paints a portrait of her own ambivalent feelings in her lyrics. Those feelings are alternately directed towards a lover or the singer’s public, and indeed those two targets at times become hard to distinguish. She sings on “HEATED” about feeling taken for granted by her man, and I can’t help feeling like we as the audience are also being called in for the warning: “Only a real one could tame me; only the radio could play me; oh, now you wish I was complacent.” That line about the radio is primarily a pun on the double meaning of the verb “play,” but it nevertheless raises the specter of the wider listenership. The sense of a more general culpability is only sharpened in the outro, as Beyoncé commentates directly on self-scrutiny and emotional whiplash that being a public figure has generated: “Dimples on my hips, stretch marks on my tits, drinkin’ my water, mindin’ my biz; Monday I’m overrated, Tuesday on my dick.”

To that point, the new life that her renaissance aims to usher in is one of greater ease and less self-diminishing perfectionism. At that notion, you (like me) might react initially with, “Beyoncé? ‘Got a lotta Chanel on me,’ vacations-at-Cannes Beyoncé? Greater ease?” And yes, she obviously benefits from the privileges of wealth. But even if one wanted to argue that this superstar has been more-than-fairly remunerated for her pains or—more trenchantly, I think—to pursue a critique of how her art has tended to present her wealth as aspirational, it would be dishonest and incurious to write off her account of enduring the strains of criticism that go hand in hand with fame just because she is also affluent.

That ambition to cultivate a less exacting relationship to her work cannot be understood outside of the historical context of the American cultural relationship to the Black female pop star. To draw on Gerrick Kennedy once again, he traces a direct line from Diana Ross to Whitney Houston to Beyoncé in an emblematic lineage of Black pop divas who were incentivized to present a circumscribed version of their Blackness that would not be too provocative or perhaps too alien to the sensibilities of white audiences. Kennedy assesses:

Beyoncé grew tired of stretching herself to appease both sides with her Diana Ross approach to pop stardom. Though she never directly pandered to white audiences, her carefully crafted image was similar to that of Whitney’s, and her apolitical stance allowed her to become the most famous entertainer on the planet. It wasn’t until she stopped caring about chasing pop charts and airplay on Top 40 radio that Beyoncé began making the most socially ambitious artistic statements of her career. […] She’s one of the most decorated artists of our time and has been making the best music of her career, but it’s no coincidence that Beyoncé crosses over far less than she did when she was calling to all the single ladies! Even after Whitney, there’s still a price to pay for the freedom of thriving because of your Blackness and not in spite of it.

(Kennedy identifies Beyoncé’s 2016 “Formation” Super Bowl performance as a turning point in the public’s perception of the singer’s entanglement with racial politics—and if you need a refresher on that nigh-decade-old controversy, refer to Jessica Williams, The Daily Show’s “Senior Beyoncé Correspondent,” for a recap.)

But what has all this got to do with the robot lady? It reflects on the theme we’ve been developing—how Futura, a character whose original narrative role was to replace laborers and steal identities, has in the hands of these artists become a tool for commenting on how identity and persona inflect their relationship to labor. First and not least is the implicit assertion that the act of performance is labor. Why else would someone invent a robot to do it? Not only to take on the physical wear and tear of dancing and singing, but to absorb the psychic damage of being in front of an audience too. For Black female performers, a part of that ask is to bear the brunt of projected discourses on the ideal or acceptable forms of femininity, of Blackness, of sexuality and queerness.

Lang’s original film concludes with Futura being burned at the stake by a mob that labels her as “a witch!” and chases her down on the steps of a church, where her pyre is quickly erected. Some other schmaltzy stuff happens too, but that final tableau of Futura burned back down to her original robot form in front of the facade of a Gothic cathedral that is somehow smack in the middle of the futuristic city feels like an unambiguous rejection of divisive, newfangled modernity and futurity in favor of tradition.

Our contemporary Futuras appear sensitive to the possibility of being rejected in as abrupt and dramatic a fashion. Of course, the “mob,” which is to say us, has now gone digital itself. Everything has, expanding exponentially the size of the potential audience for any old act, and democratizing who might serve as the performer. With that has come also the democratization of Futura’s performance anxiety, the fear of being impersonally rejected by a crowd. There are, we are all coached to be aware, potentially a lot of cameras pointing in your direction at any given moment. Social media encourages you to point one at yourself. So don’t do anything you wouldn’t want millions of people to see—but also remember to be authentic! Looking around, I think the pressure is getting to us.

“I will always love you,” Beyoncé declares on the track “MY HOUSE,” in what simply has to be a reference to Whitney’s most famous cover of that song for The Bodyguard. But rather than following up with the refrain “will always love you, will always love you,” before bidding us bittersweet goodbye, Beyoncé adds: “but I will never expect you to love me when you don’t love yourself.”

My interpretation is doubtless influenced by my particular hobbyhorse here, but I think this, in part, may be what she is thinking of, the way we are encouraged now more than ever to see ourselves through the critical eyes of real or imaginary others. Certainly, it comes across that way in the context of the concert documentary. How indeed could we truly enjoy Beyoncé, whose public image is so thoroughly mediated, when we are growing too media savvy to even give ourselves a break?

And in a world where the usual prescription for that stressor is some version of “just be yourself,” Futura offers an intriguing rebuttal: Be someone else for a while. Raise a barrier of persona between yourself and the more invasive avenues of modern life. Have fun with it; be “Cindi Mayweather,” android from the year 2719, or Queen Bey, the woman whose life is just dramatic enough to be interesting without tipping into being “tacky” or uncomfortable. Maybe that’s all true. Who’s to say? Playfulness, after all, has always animated art, and sincerity is perfectly achievable without keeping strictly, nakedly autobiographical. If strangers think they need or deserve the catharsis of you sharing your history, your intimate cares and secret desires…no they don’t. Be a dancing robot, embrace artifice. Use it to give yourself the space to love yourself. Who are you? You’re that girl. You’re an alien from outer space. You’re the queen of the night. Oh yeah…

- On that last point, the work (and so much more) has already been done by professor of music Daphne Brooks in her book Liner Notes for the Revolution, pp. 111-123. ↩︎